In 2013 Luis Alberto Jojoa (“hoh-HOH-ah) was taking classes in sample roasting, green coffee analysis, and cupping at a technical school outside of the town of Pitalito, Colombia. He had won first place in the 2006 Cup of Excellence, one of the world’s most prestigious contests for specialty producers, and yet his coffee had mostly slipped back into obscurity. Gustavo Vega, Azahar’s regional quality manager for Southern Huila, was trying to help him get his coffee back into the specialty pipeline. It was at one of the cupping tables Gustavo organized during this period that I first met Luis Alberto.

These days, fruity coffees are abundant in Southern Huila. But at the time, tasting Jojoa’s coffee from among a set of other samples from the area felt nothing short of explosive. There was a delicate floral quality to them, as well; a reminder of how much of taste is smell. The juiciness was more thirst-quenching than winey, higher toned and peachy. It hadn’t lost its coffee-likeness the way explosive coffees often do. We decided to visit Jojoa’s farm, in the hamlet of Charguayaco, at the end of a road that leads up to a little-known nature reserve called El Silencio.

Jojoa’s farm, La Perla del Otún, works its way up the steep flanks of a canyon adjacent to the one where his house is located. One plot faces southwest and the other northwest, both capturing oblique angles of equatorial sun. Jojoa acquired this land from his former boss after several years of harvesting, weeding, and pruning to compensate for the capital he could not originally offer.

Since then, he has experimented with different varieties, eventually settling on a combination of Caturra, Castillo, Ombligón, and Borbón Rosado. The two coffees released this month are a field blend of Caturra, Castillo, and Ombligón; and a single variety selection of Borbón Rosado, or Pink Bourbon. While the varieties themselves are compelling, to say the least—the field blend pleasantly vegetal, the Pink Bourbon floral and juicy—I would like to focus on the process behind them. That is what sets Jojoa’s coffees apart.

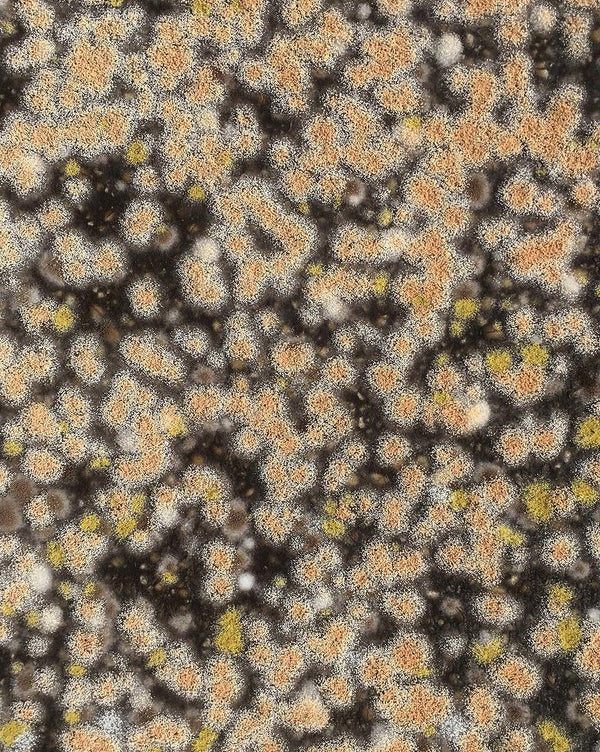

Conventional wisdom asserts that after the harvest, control is the key to quality. Once the coffee cherry has been pulped and the seeds are ready to have their sugars consumed by microbes—in what enologist Lucia Solis has referred to as microbial demucilagination in lieu of fermentation—the goal is to ensure that this process takes place in as sterile an environment as possible. And so, as Jojoa began selling his coffee for a higher price1, he retiled his fermentation tanks in white, making them easier to clean.

He also quit another habit: rather than piling one day’s picking on top of the other, letting the slimy seeds sit until the week’s picking was over and then rinsing the broken-down mucilage away (this is where washed coffees get their name from), he began to treat each batch separately, letting them sit for typically prescribed periods ranging from 24 to 48 or even 72 to 96 hours.

The results were dishearteningly monochromatic: his coffees lost the depth and transparency they had once possessed. The fruitiness still came through in some instances, but it was as if those notes were floating on top of the coffee: more “ferment-y”, less fully integrated. The cups were notably less floral, less unique from other fruity ones.

Jojoa eventually reverted to his method of piling each days’ pickings on top of each other, mixing them together in the evening but not washing them until he was done picking for the week. The results were encouraging. Then he tried something else: he stopped cleaning the tiles of his fermentation tanks, at least until the season was over. Throughout the harvest, he let local microbes build up on the walls of the two tanks, which lent a complexity to his coffee that speaks to the Charguayaco and Laboyos Valley2. In an era of infused (e.g. added fruit) and inoculated coffees (i.e. added yeast), Jojoa’s intention to return, like a hero at the end of his journey, to the old ways of processing his coffee, is hard not to compare to the decision of many natural winemakers. Whenever I taste Jojoa’s coffees these days or spend time with him on his farm, I can’t help but feel like he’s at the cutting edge of the past in the same way that natural winemakers are—placing an emphasis on time and place. In coffee, normally process is at odds with terroir, but in Jojoa’s case, it’s what brings the two together.

I love Jojoa’s coffees because they remind me that what we had is sometimes the best we’ll ever have; and that maintaining it is striving, too. Through his delicate touch and hard work, he lets you taste a bit of that natural refuge, fittingly called “El Silencio,” with its ferns and heliconias quietly growing further up the sunny canyon behind his farm.

1. A “carga” is 125 kilograms of parchment coffee, roughly the load a mule can carry on its back.

2. This year Azahar will pay Jojoa more than 4 million Colombian pesos per carga, in addition to harvesting the coffee with its team of pickers at the Manos al Grano foundation.

3. The Valle de Laboyos, where Pitalito is located, got its name from the indigenous Laboyos people that lived in the area before the Spanish arrived in the 16th Century.