The word fermentation comes from the Latin word fervere, meaning “to boil.” The ancient Romans, upon seeing vats of grapes spontaneously bubble and transform into wine, described the process using the closest analogue they could think of. And while those bubbling vats of grapes had nothing to do with boiling, they were true ferments in the scientific sense, as yeast-produced enzymes transformed the sugars in the grapes into alcohol.

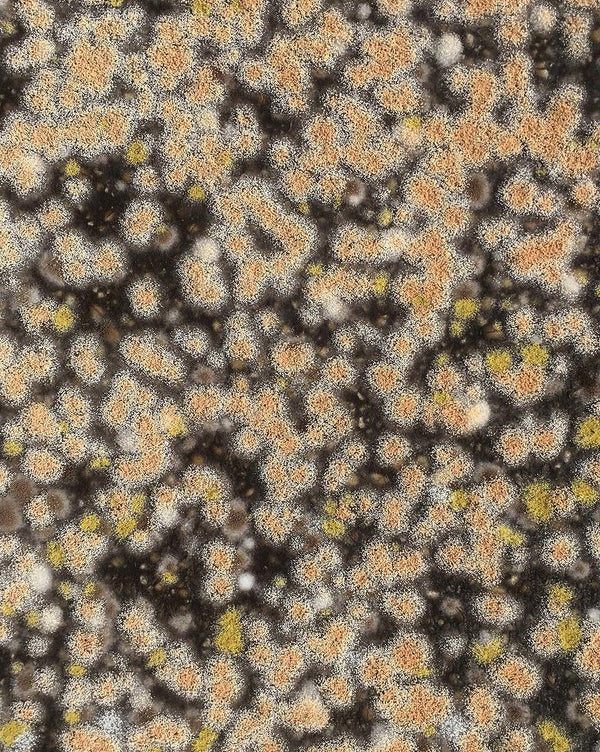

However, not all the processes we consider to be fermentation fit neatly into tidy definitions of it. For instance, while koji is faithful to the definition, Noma’s garums are not. In koji, the mold Aspergillus oryzae penetrates grains of rice or barley and produces enzymes that convert the grain’s starches into simple sugars and other metabolites. This is what’s known as a primary fermentation process. The garums in this book, on the other hand, are the product of a secondary fermentation process. To produce garum, we mix koji with animal proteins in order to take advantage of the enzymes produced during the primary fermentation process.

We don’t differentiate between primary and secondary fermentation processes in this book, but you may find it helpful to have these definitions under your belt as you find your way with fermentation.

You taste as much with your brain as you do with your tongue.

What Makes Fermentation Delicious?

Taste is a function of the human body, and to understand what tastes good to us, we have to understand its role in our evolutionary history. All our senses serve to aid in our survival. Our senses of taste and smell have been shaped over hundreds of millions of years to incentivize us to eat foods that are beneficial to our bodies. Our tongues and olfactory system are unbelievably complicated organs that take in chemical cues from the world around us and transmit that information to our brains. Taste lets us know that a ripe piece of fruit is sweet and thus full of calorie-rich sugar, or that a plant’s stalk is bitter and potentially poisonous. We are born with aversions to certain flavors (a sense that becomes reinforced by experience), leading us to gag at the stench of rotting flesh decaying at the hands of pathogenic bacteria, while we register the scent of meat roasting over fire as mouthwateringly delicious, because it indicates to our brains that we’re about to eat something

rich in proteins.

There are numerous biological processes at work in any given fermentation, but the ones that matter most to us from a taste perspective are those that break down large chains of molecules into their constituent parts. The starches in foods like rice, barley, peas, and bread are actually long chains of linked molecules of glucose, a simple sugar. Proteins, which can be found in large supply in soybeans and meat, are constructed in a similar fashion from lengthy, winding chains of amino acids—small organic molecules essential to all aspects of life on earth. One of those amino acids, glutamic acid, registers on our taste receptors as umami—the elusive, crave- able quality that connects foods like mushrooms, tomatoes, cheese, meat, and soy sauce.

So what makes fermentation so good? On their own, starch and protein molecules are too large for our bodies to register as sweet or umami-rich. However, once broken down into simple sugars and free amino acids through fermentation, foods become more obviously delicious. Koji made from rice has an intense sweetness that plain cooked rice doesn’t. Raw beef left to ferment into garum has a savoriness that speaks to us on a primitive level.

Simply put, the microbes responsible for fermentation trans- form more complicated foodstuffs into the raw material your body needs, rendering them more easily digestible, nutritious, and delicious. Our affection for the tastes those microbes produce has allowed them to evolve and stay in our company. Humans have been fermenting for so long that many of the microscopic agents responsible can be considered domesti- cated, just like household cats or dogs. But while pets can stare longingly at you if they’re hungry or cold, microbes are a bit trickier to read. It’s a mutually beneficial relationship, but one that needs a bit of work to keep everyone happy. That’s the job of the fermenter.

Proteins are made of tangled chains of amino acids, life's building blocks.

—

To keep reading: Order your copy of the The Noma Guide to Fermentation today.