Garum’s origins can be traced back to ancient Greece, Rome, Carthage and Byzantium. The Latin term “garum” was derived from the Greek word ‘garos’ (garon), a small species of fish associated with the Greeks from about the fifth century BC. The Romans produced a number of different varieties, including garum, liquamen, muria, allec and haimation. It can be hard to differentiate between the different kinds, as the names were often used interchangeably. Liquamen, for example, denotes a fish sauce made using whole fish, but it became a catch-all for any kind of fish sauce.

Since Roman times, and perhaps even earlier, garum has been extremely popular in Southeast Asia. For a period, fish sauce was used widely across Japan, Korea, and parts of China. But, beginning in the 14th century CE, soy sauce replaced it as the go-to source for savory, salty, umami.

It’s kind of astonishing: across ages and continents—well before the creation of the internet or even the advent of travel—people have been extracting umami from fish. Is it a coincidence? Inherent, somehow, in all of us?

And what would a noma garum look like?

The noma garum

We use the term garum even more loosely at noma—and we don’t just use fish to make it. Years ago, our very own Thomas Frebel was the first to suggest that we try making garums with meat rather than with fish. We’d been struggling with the question of how we could make ancient traditions like garum feel new and distinctly ours. Thomas’s suggestion proved to be a brilliant one: we tried a garum of grasshoppers, which was funky and wonderful and made us want to go down the rabbit hole.

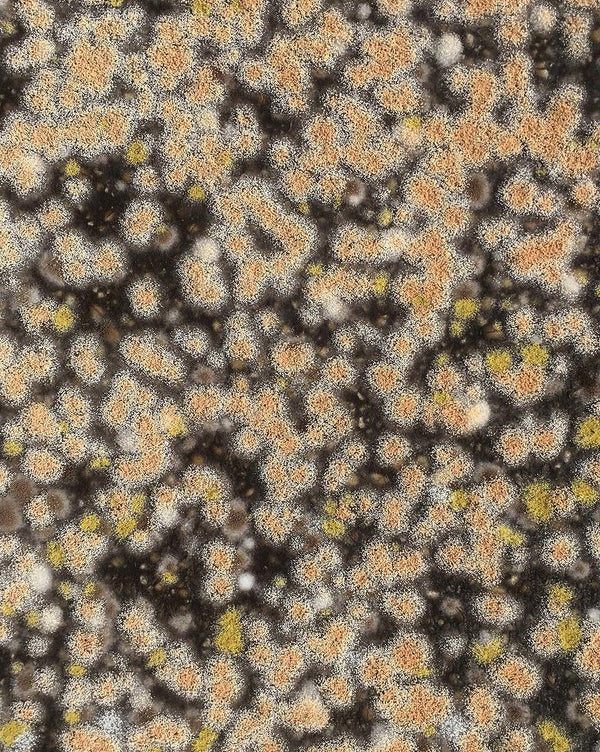

Garums are relatively easy to produce—you’re fermenting animal protein in warm conditions with salt and water—so we kept experimenting and experimenting. Pretty soon, we saw clearly that the process works just as well with meat as it does with fish. We also found that if you add koji to the equation, you can reduce the time it takes to make garum by more than half. Without the koji, many of the garums we make are technically not products of fermentation, but rather autolysis. More on this in a future Lab Dispatch.

We can now confidently say that the way that we make garum at Noma represents a novel twist on the traditional methodology; these days, garum is one of the handiest ingredients in our arsenal, even though we’re only just beginning our exploration of garum and how to wield its power.

At a restaurant like noma, where meat doesn’t play a huge role in the menu for most of the year, garums can give you the satisfaction of having eaten a piece of beef or chicken without the heaviness. When we do serve meat, we’ll often use a corresponding garum to up the intensity, whether that means adding a few drops of beef garum to strips of raw beef, or a bit of squid garum to pieces of kelp-cured squid. And, rather than reaching for a pinch of salt in a recipe, we’ll sometimes kill two birds with one stone by using garum to bring both salinity and umami.

In a way, garums have allowed us to reverse the typical hierarchy of animals and vegetables in a dish: vegetables are now the stars and meat is the seasoning. The slightest splash of garum can turn a humble soup or an unassuming slice of cabbage into something you crave.

Glutamic acid deserves a lot of the credit for this. It’s an amino acid that is present in almost all proteins and found in high concentrations in cheeses, tomatoes, seaweed, and wheat. In the making of garum, when the proteolytic enzymes cleave apart the proteins in fish or meat—or vegetables, as is the case with our plant-based Essential Mushroom Garum—it frees molecules of glutamic acid, which then give up a free positive charge to become glutamate. Glutamate, in turn, binds to mineral ions like sodium to form monosodium glutamate.

We all love MSG, no matter what some folks have to say about the subject, but some garums are better vehicles for it than others. Over the years, we’ve tried making garum with everything from squirrel and swan to spirulina and croissant. Most of them are not tasty, to say the least.

But if you never try, you never know.